Ideology

In this piece I want to discuss what might can be wrong aesthetically with art that is too subservient to a particular purpose. Specifically, how ideological elements if not handled carefully can obscure the beauty of a work.

An example of this is the hymn Jerusalem by Hubert Parry which I have already discussed in an earlier post. The repurposing of Blake’s poetry to narrowly patriotic ends does violence to the original meaning of Blake’s words and turns what is an incendiary and revolutionary piece into a work of dumb patriotism. Ideological messages must be handled subtly, especially, in the cases where the concern being referenced is current. The often what seemed relevant and perhaps provocative at the time will seem dated and even silly in the future. For example, the album Fear of a Blank Planet by Porcupine Tree. The themes of teenage alienation, drug use and addiction to the digital world and the expense of the real are heavily referenced throughout the album. At time of the albums release in 2007 it was in tune with the times and the early stages the ever expanding influence of digital technology in peoples’ lives, especially the younger generations. Looking back on it now in the era of smart phones the concerns of the album seem very prescient, but at the same, time quaint, given the total invasion of technology and particularly smart phones into our lives. In a world of constant distractions and interruptions it is harder than ever to concentrate and focus on difficult and worthwhile tasks. It is far easier to be swept away by the tide of notifications and click bait.

The music of Fear of a Blank Planet is at times so heavily weighted towards the didactic that the purely musical elements of the album are overshadowed by the repetition of the album’s themes. The music is, at times, very subtle; the lyrics are often not. It is this sentiment caused my friend to describe the album as “puerile” as the dystopian portrayal of a broken childhood it explores can seem to be and exaggerated caricature of reality. On the other hand, conflict is the essence of drama; it cannot be created by a reasonable sentiments alone. To create a compelling work a certain amount of exaggeration is often necessary. The criticism of the album I would offer is that the same message could have be conveyed less obviously. At times it feels that the listener is being beaten over the head with the same basic ideas continuously.

There is no greater example of this than Ayn Rand’s book Atlas Shrugged. What narrative that exists is poorly written and merely acts as a cypher for Rand’s clunky and simplistic philosophy. At one point a character via a radio broadcast lectures on various ideological topics for an entire chapter. No action or plot development occurs, the reader is subjected to a rambling sermon that provides among other ideological curiosities yet another superficial interpretation of The Garden of Eden.

By contrast, a work that is not guilty of this sin is The Man in the High Castle by Philip K. Dick, it explores an alternative reality where the Axis Powers have won World War II. Racism is one of the main themes of the book. Throughout the narrative the reader is given glimpses of the genocidal program the Nazis have carried out after their victory, but the audience is never shown the full extent of the horrors they have inflicted on the world. This allows the reader’s imagination fill in the gaps that the author leaves in the descriptions of these events making this aspect of the story more impactful without slowing down the plot due to historical detours. As Shakespeare once wrote “brevity is the soul of wit”.

Biography

In the age of social media the confessional and explicit seems to be prioritised over the obscure and artistic. It used to be that all you could ever find out about an artist was whatever could be gleaned from print media, the radio, and liner notes in albums. Now almost any conceivable detail of a musicians life can be googled. However, it must be said that you can be armed with all the biographical and historical information about an artist but fail to understand their work if you do not pay attention to the purely aesthetic aspects of it. It is easy to make the mistake of fallaciously linking a miscellaneous quality in a work to some biographical detail.

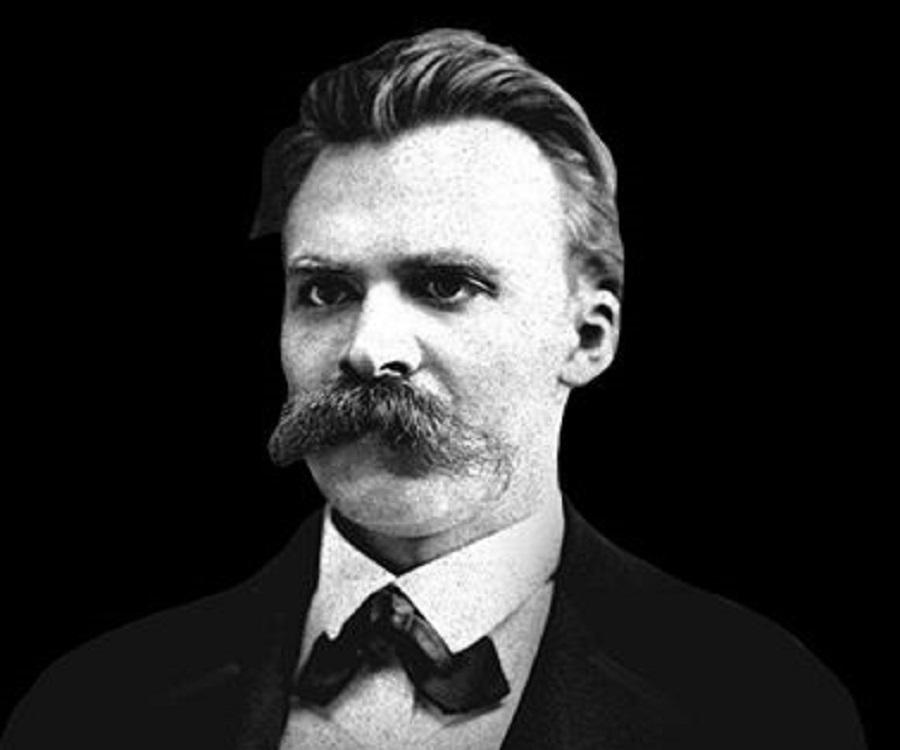

For example, Nietzsche famously went insane at the end of his life, many think this is a consequence of the nihilistic ideas he proposed, but it is also entirely possible he went mad for some other reason. Perhaps his philosophy was merely a contributing factor aggravating some existing predisposition to insanity. When considering an event of past our minds a inclined to create a coherent narrative out of events that may have been entirely disconnected. Further, there is a tendency for over time one idea or interpretation to come cemented in our thinking simply repetition. The idea that Nietzsche’s philosophy caused his madness has now been repeated so many times that is gained a level of acceptance that is merely due to constant recapitulation. This tendency is reinforced by our predisposition that once we have found a specific detail that supports our argument to “anchor” our pre-existing judgement based on it. Many people do not like Nietzsche’s philosophy as it is anti-religious and very critical of altruistic behavior. Whatever the logical merits or deficiencies of his philosophy critics of his ideas are eager to seek any route to justify their aversion to his ideas, his madness being one such detail. The example of other philosophers with a nihilistic aspect to their thinking such as Schopenhauer, who did not go insane is often ignored.

In Nietzsche’s case, I am not suggesting that it is impossible that his philosophical ideas could not have driven him to madness. Rather, I am merely cautioning against jumping to certain conclusions too easily without strong evidence.

To return to our previous topic of discussion, forcing art to serve other purposes apart from the the purely aesthetic can lead to a dilution of the work’s beauty. I must caveat what I am saying here by acknowledging that there are many good counter examples to my suggestion, the most obvious being religious art: it clearly serving an ideological purpose but is nonetheless a genre that has many works of great beauty. In my defense, I would say that in such cases the beauty of work is transcending the purely ideological, although the subject matter must of course inform any considered appreciation of a work.

Further, ignoring the purely aesthetic dimensions of art in favor of historical details can also lead to interpretive mistakes.

In the world of beauty, ideology must be a slave of the aesthetic.